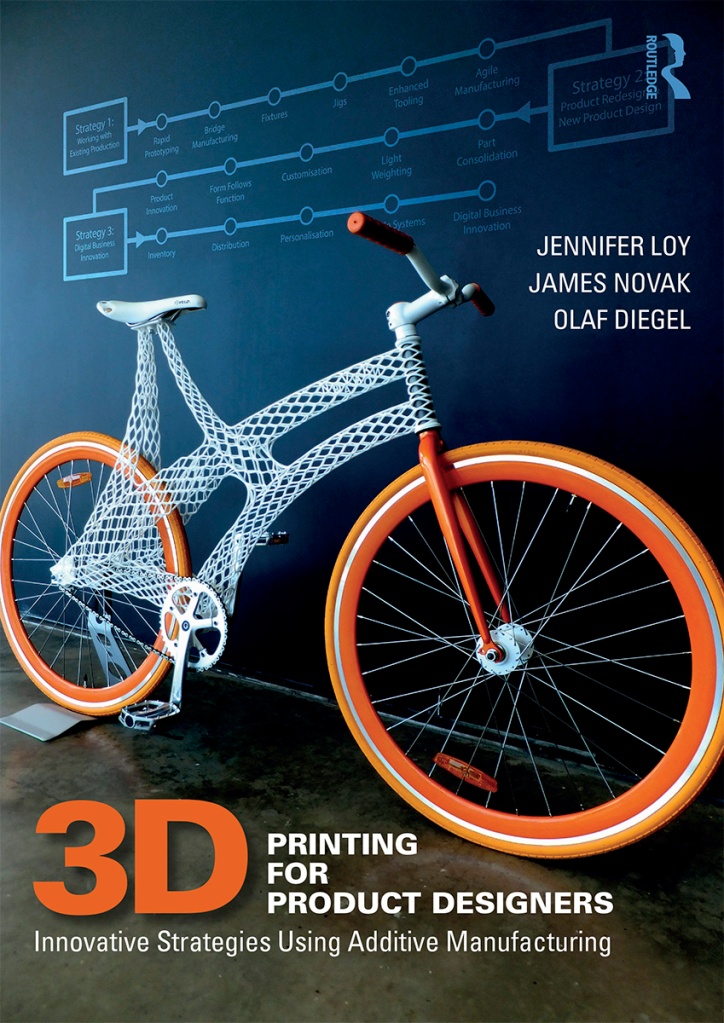

I’m extremely excited to share some news with you all! For the past 2 years I’ve been writing a book that is specifically focussed on 3D printing strategies and case studies for product designers. I’ve been lucky enough to work with Prof. Jennifer Loy and Prof. Olaf Diegel, both very well known leaders in the field. The book is called 3D Printing for Product Designers: Innovative Strategies Using Additive Manufacturing, and is now available for pre-orders direct from the publisher Routledge (at a discounted price!).

In many ways this book closes my personal first chapter in the 3D printing industry, which began in 2009, and brings together experiences and lessons learned working in industry, with industry, and on cutting-edge research projects at several of Australia’s leading universities specialising in 3D printing. Of course, my 3D printed bicycle has been a big part of that journey, and was selected by the team for the front cover, which is a real privilege. And yes, there is a detailed case study in the book that explores this project in more detail for anyone interested.

Obviously there are already some fantastic books on 3D printing, with Ian Gibson et al.’s book Additive Manufacturing Technologies probably the most well known, originally published in 2015. Our co-author Olaf Diegel also led writing a more recent book called A Practical Guide to Design for Additive Manufacturing, and 3D Hubs have a nicely illustrated book called The 3D Printing Handbook. There are others, but one thing most of these books have in common is that they’re particularly written for engineers, with lots of technical guidelines and explanations of the different 3D print technologies (which can date quickly given the rapid pace of technology developments). There isn’t a book written specifically for product and industrial designers using 3D printing, and there isn’t one that helps companies understand how to effectively adopt the technology. That’s where our book fills the gap.

The book revolves around 3 overarching strategies that can be followed chronologically, or selectively chosen depending on a company’s specific needs:

- Strategy 1: Working with existing production – includes rapid prototyping, bridge manufacturing, fixtures, jigs, enhanced tooling and agile manufacturing.

- Strategy 2: Product redesign and new product design – includes part consolidation, light weighting, customisation, form follows function and product innovation.

- Strategy 3: Digital business innovation – includes digital inventory, distribution, personalisation, scalable systems of supply and digital business innovation.

The goal is to help designers and engineers lead their company or client through a process of incremental change. This is particularly important for established companies with a workforce (or management) resistant to change. It can also be used to inform new entrepreneurial activity, allowing startups to begin at the cutting edge of digital business innovation.

Real-world case studies used to illustrate these strategies include bicycles (of course!) and other sports products, guitars, furniture, medical devices and prosthetics, jewellery, heat exchangers and more. Many of these have come from our friends and colleagues around the world, and the book features over 100 high quality colour photos to illustrate these.

The book is currently in production, so I can’t share a lot more right now, but I look forward to sharing some more detailed posts soon to give previews of different sections of the book. Stay tuned!

– Posted by James Novak

Shim was designed in

Shim was designed in