Recently there’s been quite a lot of attention on the use of 3D printing to manufacture artificial eyes (aka. ocular prostheses). This has largely been due to an announcement out of the UK that the world’s first 3D printed artificial eye was implanted in a patient.

Quite a cool milestone and application of 3D printing, and also happens to be a field I’ve been investigating for the past 6 months with some of my colleagues at the Herston Biofabrication Institute. We’ve just published a review of all research into the use of 3D printing for orbital and ocular prostheses, and you can access the full article for free here.

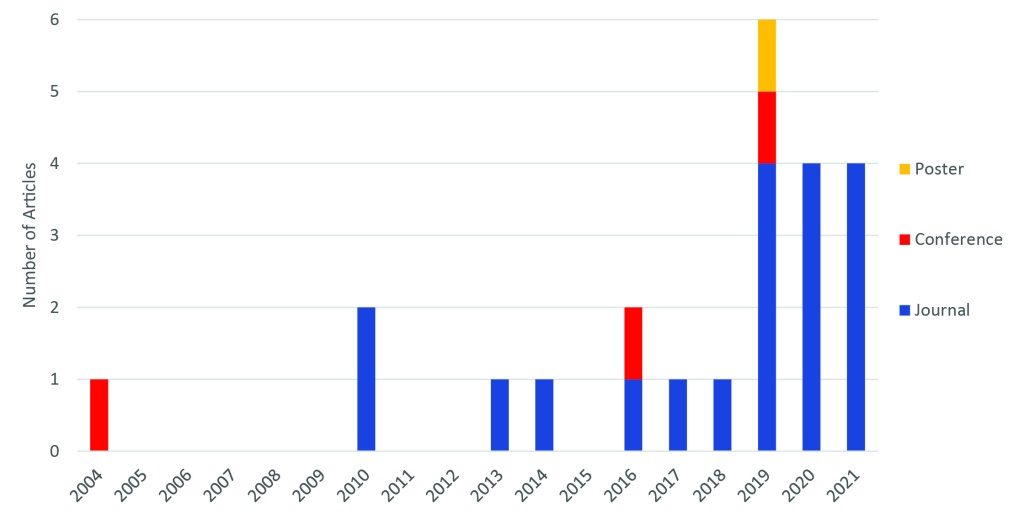

The graph above does a nice job of showing the overall trend for research on this topic, with the first ever paper dating back to 2004. Early studies like this certainly weren’t 3D printing eyes and implanting them in patients, but instead used 3D printing as part of the process, creating moulds and similar devices. The first time a 3D printed part was directly used as part of a prosthesis was in 2014.

Perhaps one of the best ways to demonstrate what is possible now using full-colour 3D print methods (material jetting) is the below video from Weta Workshop. While these may be eyes for monsters, the same principle is being used for human prosthetic eyes. One of the key differences between what Weta Workshop have achieved, and what is being done for patients, is the need for biocompatible materials, as well as the need for a patient’s eye to perfectly match their existing “good” eye.

While it’s early days in the clinical trial phase of implementing 3D printing for prosthetic eyes, there are many benefits which we summarised from our research, including:

- Manual steps in prosthesis fabrication can be replaced by digital methods, potentially saving time

- Less discomfort to patients through use of medical imaging or 3D scanning techniques

- Weight reduction compared to traditional methods

- Improved accuracy and fitting of prosthesis

- Minimised need for gluing a prosthesis to the skin

- Good realism of eye

- Ability to easily re-print the same components in the future

Of course, there are currently some limitations as well, such as:

- End-use 3D printed parts are typically not biocompatible and require coating with PMMA or used as a mould to cast with biocompatible material (although the UK trial shows that direct 3D printing of multi-colour biocompatible materials may be possible)

- Experience in computer-aided design (CAD) technology is required, which is not part of traditional skillset for prosthetist

- AM times are slow (although they can also happen overnight or while a specialist does other things)

- Rough surface quality of parts requires additional post-processing e.g. polishing

- Challenges associated with using 3D scanners e.g. patient movement or scanning anatomy with hair

- Expert manual skills are still required for some steps of the workflow

- Use of CT scanning for the purposes of creating a prosthetic increases patient exposure to potentially harmful radiation

Research to-date has been limited to small case studies and engineering experiments, making it difficult to understand whether outcomes will translate to the clinical context. It will be great to see how the UK clinical trial progresses, and hopefully provides improved outcomes for patients. Let’s watch this space!

– Posted by James Novak