Authors: James Novak, The University of Queensland | Andrew Novak, The University of Technology Sydney

** Please note: this is a copy of an article I wrote for The Conversation, published on 3rd September, 2021, and is shared under a CC-BY-ND license. You can access the original article by clicking here.**

Major sporting events like the Paralympics are a breeding ground for technological innovation. Athletes, coaches, designers, engineers and sports scientists are constantly looking for the next improvement that will give them the edge. Over the past decade, 3D printing has become a tool to drive improvements in sports like running and cycling, and is increasingly used by paralympic athletes.

The Paralympics features athletes with a diverse range of abilities, competing in a wide range of different categories. Many competitors use prosthetics, wheelchairs or other specialised components to enable them to perform at their best.

One interesting question is whether 3D printing widens or narrows the divide between athletes with access to specialised technologies, and those without. To put it another way, does the widespread availability of 3D printers — which can now be found in many homes, schools, universities and makerspaces — help to level the playing field?

Forget mass production

Mass-manufactured equipment, such as gloves, shoes and bicycles, is generally designed to suit typical able-bodied body shapes and playing styles. As such, it may not be suitable for many paralympians. But one-off, bespoke equipment is expensive and time-consuming to produce. This can limit access for some athletes, or require them to come up with their own “do-it-yourself” solutions, which may not be as advanced as professionally produced equipment.

3D printing can deliver bespoke equipment at a more affordable price. Several former paralympians, such as British triathlete Joe Townsend and US track athlete Arielle Rausin, now use 3D printing to create personalised gloves for themselves and their fellow wheelchair athletes. These gloves fit as if they were moulded over the athlete’s hands, and can be printed in different materials for different conditions. For example, Townsend uses stiff materials for maximum performance in competition, and softer gloves for training that are comfortable and less likely to cause injury.

3D-printed gloves are inexpensive, rapidly produced, and can be reprinted whenever they break. Because the design is digital, just like a photo or video, it can be modified based on the athlete’s feedback, or even sent to the nearest 3D printer when parts are urgently needed.

Read more: Paralympians still don’t get the kind of media attention they deserve as elite athletes

Harder, better, faster, stronger

An elite athlete might be concerned about whether 3D-printed parts will be strong enough to withstand the required performance demands. Fortunately, materials for 3D printing have come a long way, with many 3D printing companies developing their own formulas to suit applications in various industries – from medical to aerospace.

Back in 2016, we saw the first 3D-printed prosthetic leg used in the Paralympics by German track cyclist Denise Schindler. Made of polycarbonate, it was lighter than her previous carbon-fibre prosthetic, but just as strong and better-fitting.

With research showing sprint cyclists can generate more than 1,000 Newtons of force during acceleration (the same force you would feel if a 100-kilogram person were to stand on top of you!), such prosthetics need to be incredibly strong and durable. Schindler’s helped her win a bronze medal at the Tokyo games.

More advanced materials being 3D printed for Paralympic equipment include carbon fibre, with Townsend using it to produce the perfect crank arms for his handbike. 3D printing allows reinforced carbon fibre to be placed exactly where it is needed to improve the stiffness of a part, while remaining lightweight. This results in a better-performing part than one made from aluminium.

3D-printed titanium is also being used for custom prosthetic arms, such as those that allow New Zealand paralympian Anna Grimaldi to securely grip 50kg weights, in a way a standard prosthetic couldn’t achieve.

Different technologies working together

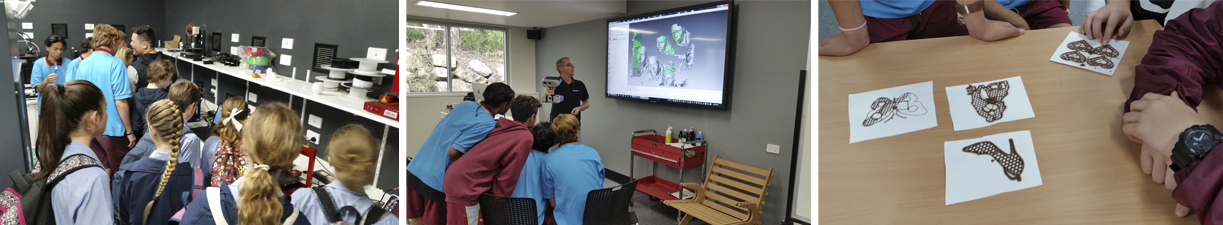

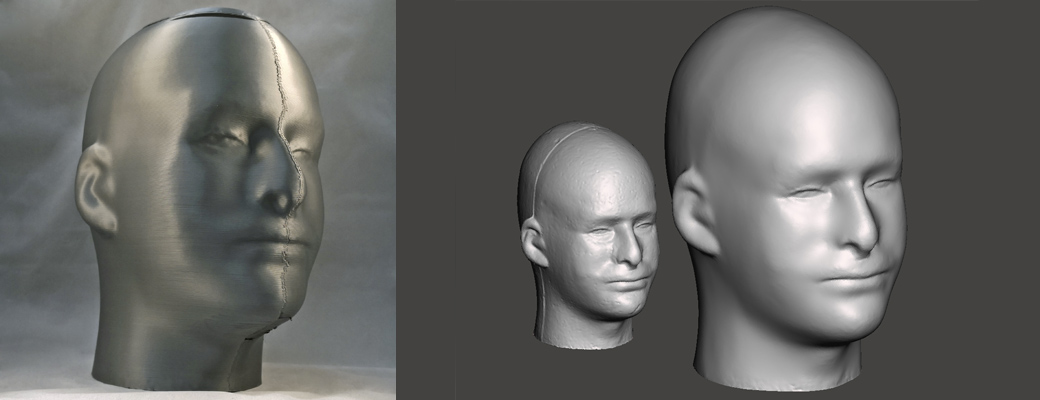

For 3D printing to deliver maximum results, it needs to be used in conjunction with other technologies. For example, 3D scanning is often an important part of the design process, using a collection of photographs, or dedicated 3D scanners, to digitise part of an athlete’s body.

Such technology has been used to 3D-scan a seat mould for Australian wheelchair tennis champion Dylan Alcott, allowing engineers to manufacture a seat that gives him maximum comfort, stability and performance.

3D scanning was also used to create the perfect-fitting grip for Australian archer Taymon Kenton-Smith, who was born with a partial left hand. The grip was then 3D-printed in both hard and soft materials at the Australian Institute of Sport, providing a more reliable bow grip with shock-absorbing abilities. If the grip breaks, an identical one can be easily reprinted, rather than relying on someone to hand-craft a new one that might have slight variations and take a long time to produce.

Read more: 3 reasons why Paralympic powerlifters shift seemingly impossible weights

All these technologies are increasingly accessible, meaning more non-elite athletes can experiment with unique parts. Amateurs and professionals alike can already buy running shoes with 3D-printed soles, and 3D-printed custom bike frames. For those with access to their own 3D printer, surf fins, cycling accessories and more can be downloaded for free and printed for just a few dollars.

However, don’t expect your home 3D printer to be making titanium parts anytime soon. While the technology is levelling the playing field to a certain extent, elite athletes still have access to specialised materials and engineering expertise, giving them the technological edge.

This article was co-authored by Julian Chua, a sports technology consultant at ReEngineering Labs and author of the Sports Technology Blog.

I

I As explained in further detail in my

As explained in further detail in my

To the right are the dimensions of the ceiling light fixture within which the sea urchin light comfortably fits. The light itself is a standard B22 fitting, so the sea urchin can comfortably fit most standard interior lights. However, if you have a different sized fitting, or want to fit it over an existing lamp, you can easily scale the design up or down to suit your needs. I’ve already fitted one of the early small test prints over an old Ikea lamp, it just sits over the top of the existing frame. In total I’ve now installed 5 of the large ceiling light covers in my house, and am planning a new design to replace some of the others (my house is full of this terrible cheap fitting!).

To the right are the dimensions of the ceiling light fixture within which the sea urchin light comfortably fits. The light itself is a standard B22 fitting, so the sea urchin can comfortably fit most standard interior lights. However, if you have a different sized fitting, or want to fit it over an existing lamp, you can easily scale the design up or down to suit your needs. I’ve already fitted one of the early small test prints over an old Ikea lamp, it just sits over the top of the existing frame. In total I’ve now installed 5 of the large ceiling light covers in my house, and am planning a new design to replace some of the others (my house is full of this terrible cheap fitting!).

After some ideas from the

After some ideas from the